Imagine this. You’re chilling out at home, innocently scrolling through social media. After the important tasks of looking at pics of puppies and your neighbour Julie’s all-inclusive Turkish holiday, something emerges from the depths of the Metaverse…

Your great-uncle Leslie has shared a scientific journal article that ‘exposes the truth’ against what you thought to be a widely accepted fact among the scientific community. You’ve never been one for conspiracy theories, so open it and give a flick through for a laugh, expecting poor old Lez to have simply misunderstood a few fancy technical words in the ‘conclusion’.

You read it… he’s correct. The crazy claims are there and clear as day, sitting proudly in a journal! But how? Aren’t all journals bastions of excellence? Surely, they would never spread fake news? Panic sets in.

Truth is, a lot of not-so-great science can wander its way into journals. Being able to pick credible sources of information is a priceless, yet tricky skill to learn, even for the scientifically literate. With all things considered, here’s a handy guide of things to look out for when critically analysing scientific literature.

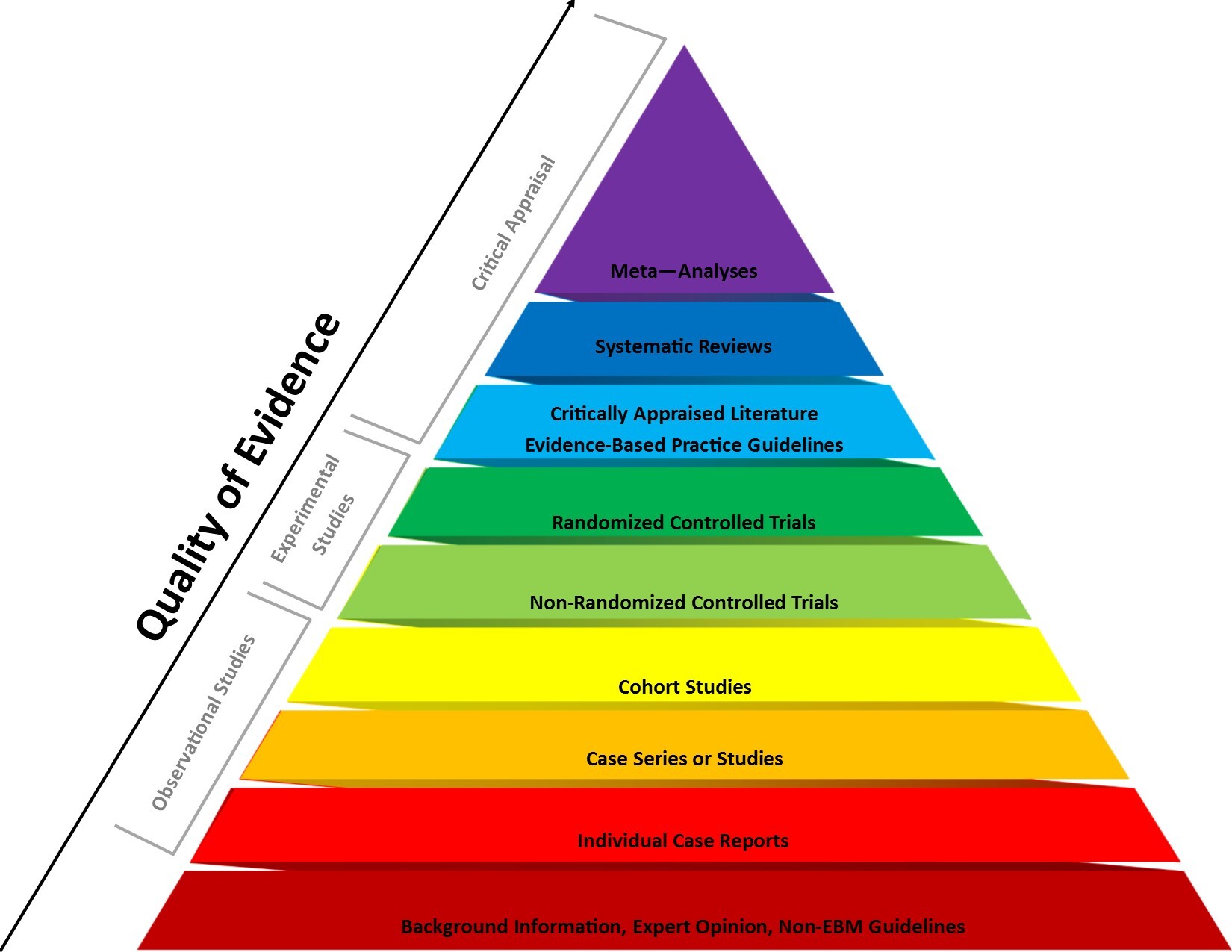

Analyse the study design

Not all medical research is created equal. The hierarchy of clinical evidence is a system that categorises different types of clinical evidence based on scientific rigour. This hierarchy helps clinicians and researchers assess the reliability and validity of evidence when making healthcare decisions.

If the paper you’re reading is investigating the efficacy of a treatment in humans, the gold standard is a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Double-blind studies ensure that neither patients nor investigators are aware of who’s receiving the study drug or the dud, to counteract placebo effect — an ever-present, mysterious power in the brain that can convince your body that you’re receiving a positive effect from a treatment when in reality you’re not. Less robust publications such as case studies and open-label trials have their merits, but have significant potential to be influenced by the placebo effect and other biases, so be wary.

Does the clinical trial need to compare the study drug against a placebo to be believable? Not quite. In the case of patients with active disease, participants could be given the “standard of care” treatment instead, and the results are still trustworthy, because they’re establishing a comparison with a control agent that has already been approved for treating that specific condition.

Compare the patient characteristics

Patient demographics are usually listed in clinical trial papers, so take a gander at them. Are baseline characteristics similar between treatment groups? For instance, does the mean age of patients in one cohort significantly differ from that of the other? This asymmetry could be an issue if we argue that older adults are more likely to have poorer health, which could potentially impact whatever the trial is investigating.

Age isn’t the only factor that can impact the outcome of a study; regional variations in the patient population can also influence findings in surprising ways. During some research concerning the anti-parasitic treatment ivermectin for COVID-19, the authors mapped the drug’s effectiveness in different regions of the world where the prevalence of a particular parasite known as Strongyloides also varied [1]. The meta-analysis found that ivermectin was effective at reducing the mortality risk in human trials, but only in regions where Strongyloides was endemic. Ivermectin was protecting weakened COVID-19 patients, but solely through preventing a parasitic infection progressing.

Also, are any human patients involved at all? All research has to start somewhere, but what might work in a test tube or animal model, is in no way guaranteed to work in humans. Save your excitement for when a promising new treatment has undergone some rigorous testing in later phases of human testing, Leslie.

Evaluate publication bias

For a variety of reasons, articles are more likely to be published where null hypotheses are rejected (i.e. where the tested scientific relationship is shown to be real). Consequently, there may be a wealth of solid evidence where nothing ‘exciting’ is found (e.g. new drug X has no effect on population Y). It’s a complex topic, and there are ongoing attempts to tackle the problem, but do bear it in mind.

Meta-analyses are types of publications that aim to collect all available quality evidence to ask a question (e.g. ‘does drug X actually work?’). Frustratingly, these still can be suspiciously selective. The good news is there are some well-known contributors out there who are revered for the quality of their meta-analyses, e.g. Cochrane reviews [2].

Inspect for author conflicts of interest

Let’s pretend that the article great-uncle Leslie shared was conclusive proof that eating Dunkin’ Donuts would make your face turn blue. If the lead author of that paper was a major stakeholder for their competitors Krispy Kreme, wouldn’t that send alarm bells ringing?

The same goes for real scientific research. A good-quality journal should always include a section for authors’ conflicts of interests. Such declarations are not necessarily bad things — but it is important to understand their context. However, if there is any juicy info that hasn’t been publicised, then that starts looking a bit more suspicious.

Critique the stats

Stats are crucially important in science. Make sure that any relevant claims are backed up by data with statistically significant p-values, which indicates the likelihood of an outcome occurring by chance.

For those that want to get proper nerdy, have a look at whether the correct statistical tests and methods have been used for the data in question. T-tests, chi-square, Bonferroni correction, ANOVA… oh gosh I’m getting flustered just thinking about them all.

Check for retractions

If it turns out a journal article contains errors, if the data aren’t robust, or there are other issues, it can be ‘retracted’. A retracted article is no longer considered part of the journal it had initially been published in. Even then it may lurk about on the web, like a ghost, but you can ‘bust’ those submission apparitions with DATA. Have an investigate online — databases like PubMed and websites (e.g. www.retractionwatch.com) can tell you if something has been retracted, and quite often why.

Consult a checklist

If you want to get super stuck in and make sure you cover all bases, then it’s your lucky day! There are some hugely detailed checklists available online by the Cochrane organisation to work out the risk of bias in different types of studies [3]. Other, less detailed versions are available elsewhere online which cover the main principles.

Listen out for discussion

You may not need to wear your Sherlock deerstalker hat and lab coat when the scientific community can do the hard work for you! Published papers that go against the narrative or make big claims can often get a lot of attention. This naturally invites scrutiny from across the scientific community, which in turn sometimes reveals shocking findings, so look out for them.

Scientists by nature love analysing. So, if you keep one ear to the ground, anything sparking significant discussion is probably worth checking out. Then you can assess the details and the data for yourself.

Predatory journals and publishers

Predatory publishers have been defined as:

[4]

“…entities that prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship and are characterized by false or misleading information, deviation from best editorial and publication practices, a lack of transparency, and/or the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices”

Predatory publishers can catch all of us — including scientists. One study found that out of 46,000 Italian researchers, 5% had published in such journals [5]. It’s a difficult job to know who is friend or foe, and there are countless ways to be deceived by predatory publishers. The important thing to take home is that there are blacklists/whitelists from a handful of organisations that can help you ascertain the genuine article (sorry!) from an unscrupulous predatory publisher. So be cautious, and don’t take things at face value.

Conclusion

Summing everything up, know that it’s totally okay to have a difference of opinion with your great-uncle Leslie. However, remember that spreading misinformation can be harmful. Be aware of author bias and transparency and appraise all the data before reaching conclusions. So, keep an open mind, keep it objective, and keep it honest. You’re on your way towards becoming an informed judge of quality science.

References

- Bitterman A et al. Comparison of Trials Using Ivermectin for COVID-19 Between Regions With High and Low Prevalence of Strongyloidiasis. Jama Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e223079

- Cochrane. Cochrane Library. Available at: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/. Accessed 19th August 2022

- University of Bristol. Risk of bias assessment tools. Available at: https://www.riskofbias.info. Accessed 19th August 2022

- Grudniewicz A et al. Predatory journals: no definition, no defence. Nature. 2019;576(7786):210-212

- Bagues M, Sylos-Labini M & Zinovyeva N. A walk on the wild side: ‘Predatory’ journals and information asymmetries in scientific evaluations. Research Policy. 2019;48(2):462-477