We’re on a mission to transform healthcare communications worldwide, providing fearsome medical communications that pack a punch.

We’re a specialist content-first medical communications agency delivering first-class scientific and creative services for medical affairs and marketing teams in health, wellness, veterinary, and medicine, backed by an award-winning culture cultivated to help people shine. Together we can make positive change for patients, healthcare professionals, our teams, and the industry.

Open the door to big brains galore, and work with our talented, fun, and motivated team that’s raring to bring your communications to life. We’ve worked on almost every therapy area known to human and animal healthcare, with bucket-loads of lived communications experience. And we’re based all over the world, giving you access wherever you are. There’s truly something for everyone.

We mix writing, science, health, and creative for medical affairs and marketing teams in pharma, biotech, medtech, veterinary, CROs, and healthcare agencies. We can support across the full spectrum of medical communications, from publications and plain language summaries to events and e-learning to sales and marketing tools, working within every stage of a product’s lifecycle.

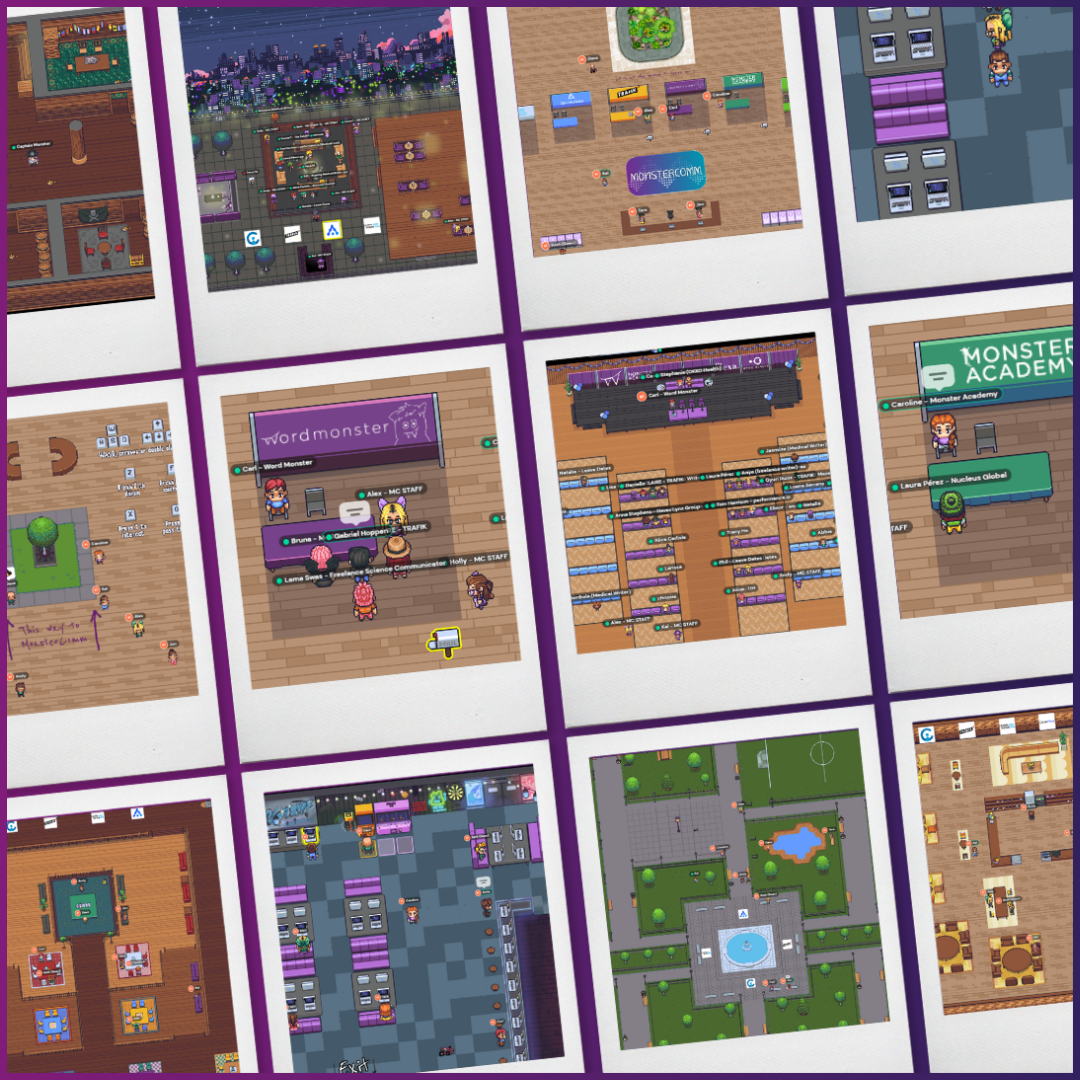

We create and host groundbreaking virtual conferences inside virtual 2D worlds, showcasing the latest in digital innovation and gamification to leaders, communicators and professionals who work in healthcare, through to stand-out careers fairs dedicated to helping aspiring medical writers break into the industry.

We attend and speak at all kinds of healthcare events, giving industry-leading talks, thought‑leading ideas on panels, specialist lunch and learns, and even deliver complimentary team building sessions to existing clients. Check out the latest event we hosted in 2D that has now been nominated for a PM Society award!

Not all heroes wear capes, and thankfully not all scientists wear lab coats. If you’re more into delivering exceptional communications than receiving them, then join our troop. We’ve created an award-winning culture that attracts and nurtures top talent, granting us the power to deliver exceptional work for our clients.

If your brain gets hungry for insights, creativity, trends, innovation, technology, culture and all things med comms and medical writing then you’d better prepare it for a feast. We’ve got top tips, tricks and ideas coming at you from our medical writing experts, cutting‑edge opinion pieces on the latest industry trends and news, spotlights about our life-first approach to work and wellbeing, and hot-off-the-press headlines coming straight out of the monsterverse.

We love hearing from clients who think we’d be a good culture fit for them and their organisation. If you already have a project in mind or if you’d just like to find out more about us and explore ideas, then feel free to reach out anytime. You can fill in the form here or contact us directly with the details below. We don’t bite, much.